By Darioush Bayandor

Throughout centuries female literally talents in Iran have been quashed and sidelined in the male-dominated socio-cultural environment of the country. Poetry is a distinct part of Iran’s cultural identity yet only five percent of some 8000 catalogued poets since the tenth century are females. Among female literary profiles in the earlier centuries two earned lasting celebrity. Both belonged to the wider cultural sphere of the Persian-language which no longer corresponds to the present-day geographical boundaries. Mahsati Ganjavi, was a twelve-century poetess living in Ganje (in to-day’s Azerbaijan) while the semi-legendry Rābe’eh Balkhi (bint Kaab) lived in or around the tenth century in Balkh (in to-day’s Afghanistan). Little of their poetry has survived and the account of their lives is shrouded in fables. This article is an introductory focus on five modern era female icons who earned fame – some stardom – blending literally talents with an ability to rise above societal inhibitions and taboos.

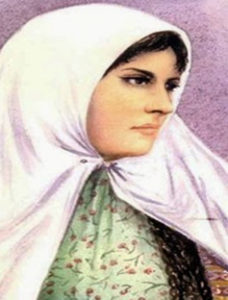

- Tahereh Qorrat’ul-Ayn; a Forbidden Legend

The nineteen-century Bābi activist-poet, Qorrat’ul-Ayn (1814/17-1852), blessed with rare beauty, blended literary talent with passionate beliefs and unorthodox life-style, a combination that makes her sui generis in true since of the term.

Born Fatimah Baraghani in Qazvin in 1814/17 to devout Shia Moslem parents – her father was a mujtahid – Qorrat’ul-Ayn broke out of the straightjacket of family conformism to become a passionate adept of the newly emerged Bābi faith, travelled extensively and was the first ever female theologian teaching in a Karbala seminary.

Born Fatimah Baraghani in Qazvin in 1814/17 to devout Shia Moslem parents – her father was a mujtahid – Qorrat’ul-Ayn broke out of the straightjacket of family conformism to become a passionate adept of the newly emerged Bābi faith, travelled extensively and was the first ever female theologian teaching in a Karbala seminary.

Facts about her life and poetry are not uncontested or free from partisan embellishment. What is certain is that Qorrat’ul-Ayn was a woman of unmatched courage with strong impulses who did not let herself entrapped in her conservative environment. She dared openly denounce polygamy and dropped her veil before a gathering of male Babi militants in Badasht village in Semnan, shortly before being arrested in 1850 for her religious activism – Babism was and remains a heretical sect by the state and the clergy in Iran. That defiant act earned her the title of Tahereh or the immaculate from the Babi sect leader, Seyyed Mohammad-Ali, better known as the ‘Bab’. Her title, Qorrat’ul-Ayn means ‘the light of the eye’, which may bear testimony to her glaring beauty. According to going tales, the young Qajar monarch, Nasser’uddin Shah, offered to wed her after her arrest which she refused. Qorrat’ul-Ayn was to be executed two years later in massive government purges of the Babi sect adherents incited by the ulama.

Little of her poetry and writings survived those purges; some were destroyed by her own disgruntled family, making some of the sonnets that bear her name apocryphal. Qorrat’ul-Ayn became a forbidden legend, a feminist of a different kind and definition nearly a century before Virginia Woolf.

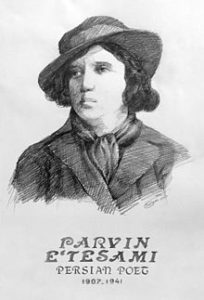

- Parvin Etessami, a Harbinger

In many ways Parvin Etessami (1907–1941) symbolized the newly enhanced status of women in the early decades of the twentieth century. Born in Tabriz to a notable family of literati from Ashtian, she was raised and schooled in the capital Tehran. She was able to pursue her schooling in the American Girl’s college and work as a librarian in Tehran’s high institute of teacher’s training (daneshsaray’e āli). Parvin, whose given name was Rakhshandeh, was the first female Iranian poet acknowledged and acclaimed by the literary milieus of her time.

In many ways Parvin Etessami (1907–1941) symbolized the newly enhanced status of women in the early decades of the twentieth century. Born in Tabriz to a notable family of literati from Ashtian, she was raised and schooled in the capital Tehran. She was able to pursue her schooling in the American Girl’s college and work as a librarian in Tehran’s high institute of teacher’s training (daneshsaray’e āli). Parvin, whose given name was Rakhshandeh, was the first female Iranian poet acknowledged and acclaimed by the literary milieus of her time.

She is often depicted as an establishment profile given her family background. Even if low-keyed and mild-mannered, she nonetheless retained a non-conformist posture during the peak of the authoritarian rule by Reza Shah. She is said to have turned down a position as preceptor and governess in the Pahlavi court and to have declined a crown decoration bestowed on her in recognition of her literary achievements. However, when in 1936 the Shah decreed European dress code for women and banned the veil, Parvin was elated and lauded Reza Shah. In a piece titled ‘zan dar Iran’ (women in Iran) she expressed her praise in her classical rhymed sonnet style:

چشم دل را پرده میبایست اما از عفاف

چادر پوسیده را بنیاد مسلمانی نبود

خسروا ، دست توانای تو آسان کرد کار

ورنه در این کار سخت امید آسانی نبود

شه نمی شد گر در این گمگشته کشتی ناخدای

ساحلی پیدا از این دریای طوفانی نبود

Chastity is not assured by that rotten veil,

Which has no real place in the Moslem faith,

O’ you the King, Your able hand eased our strain,

Muddling through that path would have otherwise been hopeless.

If the Shah would not be at the helm of this strayed vessel

No shore would have appeared in the horizon.

Parvin’s anthology, comprising over 600 sonnets composed in classical format, was published in Tehran not long before her death from typhoid at the age of thirty-four.

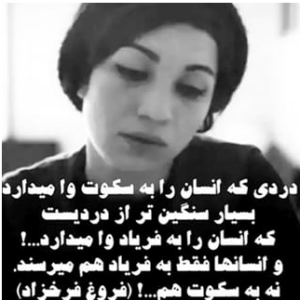

- Forough Farrokhzad; Braving the Forbidden

Still the most idolized female Iranian poet of all times – acclaimed as a shining star of modern poetry – is Forough Farrokhzad (1935–1967). Her exquisite poetry with a distinct feminine fragrance mirrored the insecure, wistful female poet with a rebellious spirit who stood up to outworn societal mores. In a piece titled ‘gonah’ (the sin) she sang, “I sinned, a joyous sin, in the warm loving embrace of a man”; she sent shockwaves across conservative milieus, notably the ulama, whose hypocrisy she mockingly commented on in a separate poem.

Still the most idolized female Iranian poet of all times – acclaimed as a shining star of modern poetry – is Forough Farrokhzad (1935–1967). Her exquisite poetry with a distinct feminine fragrance mirrored the insecure, wistful female poet with a rebellious spirit who stood up to outworn societal mores. In a piece titled ‘gonah’ (the sin) she sang, “I sinned, a joyous sin, in the warm loving embrace of a man”; she sent shockwaves across conservative milieus, notably the ulama, whose hypocrisy she mockingly commented on in a separate poem.

آن اتشی که در دل ما شعله میکشید

گر در ميان دامن شيخ اوفتاده بود

ديگر بما كه سوخته ايم از شرار عشق

نام گناهكاره رسوا نداده بود

“The flame that flares in my heart,

Had it lit the sheikh’s cloak,

Would he still call me Sinful and unchaste?”

Born to a middle class family – her father was an Army colonel – Forough married at a young age but could not obtain guardianship of her baby-boy when divorced four years later. Autodidact she joined the new literary wave in post-second war years in Iran, shedding the straightjacket of rhymed classical poetry. Forough published her first poetry book, Asir,(in bonds) in 1952 where she echoedthe boredom of life with a man she had ceased to lovewhile giving free rein to desires she pined for. Four more poetry books were to be published from 1956 to 1963;the best knownand the most acclaimed–titled tavalodi digar (a new birth) – heralded a new literary departure but also recovery from chronic despair that drove her to attempt suicide two years earlier.There she echoes her preoccupation with womanhood in Iran’s patriarchal society and reveals strong feminist streaks. About the same time she coproduced an award-winning documentary film,khaneh siah ast (the house is dark) depicting the tragedy of leprous women kept in isolation in a medical facility close to Tabriz in Azerbaijan.Her poetry has been translated into nine foreign languages.

Born to a middle class family – her father was an Army colonel – Forough married at a young age but could not obtain guardianship of her baby-boy when divorced four years later. Autodidact she joined the new literary wave in post-second war years in Iran, shedding the straightjacket of rhymed classical poetry. Forough published her first poetry book, Asir,(in bonds) in 1952 where she echoedthe boredom of life with a man she had ceased to lovewhile giving free rein to desires she pined for. Four more poetry books were to be published from 1956 to 1963;the best knownand the most acclaimed–titled tavalodi digar (a new birth) – heralded a new literary departure but also recovery from chronic despair that drove her to attempt suicide two years earlier.There she echoes her preoccupation with womanhood in Iran’s patriarchal society and reveals strong feminist streaks. About the same time she coproduced an award-winning documentary film,khaneh siah ast (the house is dark) depicting the tragedy of leprous women kept in isolation in a medical facility close to Tabriz in Azerbaijan.Her poetry has been translated into nine foreign languages.

ForoughFarrokhzadmesmerized generations of the Iranian youth, transcendingpolitical upheavals which have traversed the country since her premature death in 1967, aged 32. Her deathresulted from a car accident in a cold February day in the Tehran suburbs. Behind the wheel she had tried to avert a head-on collision with a school bus.

- Simin Behbahani; a Woman for all Seasons

Among female literary icons Simin Behbahani (1927-2014) stands out for having known and worked in two distinct Iranian societies before and after the Islamic Revolution. Her flourishing career as poet, lyrist, social commentator and salaried college teacher in effect traversed through the revolutionary era but assumed dimensions which made her one of the most influential literary figures of the contemporary Iran.

Among female literary icons Simin Behbahani (1927-2014) stands out for having known and worked in two distinct Iranian societies before and after the Islamic Revolution. Her flourishing career as poet, lyrist, social commentator and salaried college teacher in effect traversed through the revolutionary era but assumed dimensions which made her one of the most influential literary figures of the contemporary Iran.

Unlike nearly all surviving notables in the artistic community before the revolution, Simin eschewed exile and remained in Iran. She was grudgingly tolerated by the ruling circles but lionized for her literature of dissent by intelligentsia on the other side of the fault-line. In this sense, she remains a living testimony to the bipolar character of the present-day society in Iran.

Twice a candidate for Nobel Prize for literature, Simin Behbahani became the laureate of several other literary and freedom international awards including Carl von Ossietzky award by the International Commission of Human Rights in 1999. As a token of solidarity with the Iranian people, President Barak Obama cited a snippet of one her verses in his presidential Norooz message in March 2011.

Simin was born in Tehran to a family of literati. Her journalist father, Abbas Khalili, was a notable literary figure on his own right while her erudite mother is counted among the pioneers of women movement in the post-constitution era early in twentieth century. Simin’s career as poet began at a young age, her first poem having been published at the age of 14. Her poetry shifted from the free style, characteristic of post-war trends, to the more traditional rhymed sonnet format but her language and thoughts remained innovative and refreshingly feminine. Her works comprising more than 600 sonnets and other verses have been published in a streak of poetry books and anthology from 1951 to 2003. Themes during her youth, other than romantic songs, echoed her preoccupation with the social ills and the precariousness of the feminine condition; they took on political coloring in post-revolution years often expressed in a melancholic language about the lost paradigms. The passage below, from a wistful patriotic poem, is representative of her latter period.

دوباره میسازمت وطن!

اگر چه با خشت جان خویش

ستون به سقف تو می زنم،

اگر چه با استخوان خویش.

دوباره می بویم از تو گُل،

به میل نسل جوان تو

دوباره می شویم از تو خون،

به سیل اشک روان خویش.

دوباره ، یک روز آشنا،

سیاهی از خانه میرود

به شعر خود رنگ می زنم،

ز آبی آسمان خویش

I shall rebuild you, my homeland!

Even if the bricks were made from my ashes.

I shall buttress your roof,

Even if the pillars were made out of my bones.

I shall smell your followers,

And select the fragrance favoured by your youth.

I shall wash the blood off your face,

With torrentscoming down from my eyes.

One day again, soon, the darkness shall vanish from this house,

And I shall paint my poetry,

With the blue colour of your skies.

- The Younger Generation of Female Poets in Iran

In the contrasted and dual makeup of the Iranian society today, the touch stone to judge the quality of literary output has ceased to be gender-based, a progress!

The paradox arises from a little-understood specificity of Iran under the Islamic Republic. The intelligentsia and the digitally-connected youth hold a distinct vista that spans a cultural field from Pasargadae to Silicon Valley. A deep fault-line separates them from the conservative strata yet pragmatism and expediency by the ruling clerics has given rise to a kaleidoscopic environment in which dissimilar human species coexist in an unlikely symbiosis. The literary milieu is tolerated as long as their output poses little or no threat to fundamentals of the faith-based rule. Though the separation of spheres reflects a degree of maturity attained over the previous four decades, the limits of tolerance remain blurred. This means that dissident profiles of Simin Behbahani stamp thread a fine line.

Hila Sadighi, a New Idol

An Iranian scholar, Professor Rouhangiz Karachi, has catalogued 120 female poets presently living in Iran. Their identity and literary output however remain largely unknown to millions of first and second-generation Iranian living abroad, a regrettable lacuna that must be addressed in coming years.

One notable exception is the young poetess Hila Sadighi whose poetry – colored green after the suppressed youth movement in June 2009 – has traversed frontiers to make her a social media sensation. Her best known monody, lamenting the fall of a phantasmal classmate – whom many associate with the iconic martyr of Green Movement, Neda Agha-Soltan – has been readapted into French and English languages for the Iran-Etude readership. For Hila’s original poem, click here(1) Do you still love Iran (original version). For the English re-adaptation, click here(2) Do you still love Iran (english version). For the French, click here(3) Aimes-tu toujoursl’Iran (version francaise)

One notable exception is the young poetess Hila Sadighi whose poetry – colored green after the suppressed youth movement in June 2009 – has traversed frontiers to make her a social media sensation. Her best known monody, lamenting the fall of a phantasmal classmate – whom many associate with the iconic martyr of Green Movement, Neda Agha-Soltan – has been readapted into French and English languages for the Iran-Etude readership. For Hila’s original poem, click here(1) Do you still love Iran (original version). For the English re-adaptation, click here(2) Do you still love Iran (english version). For the French, click here(3) Aimes-tu toujoursl’Iran (version francaise)